Recording on a Budget: How to Write a Song With 16 Tracks

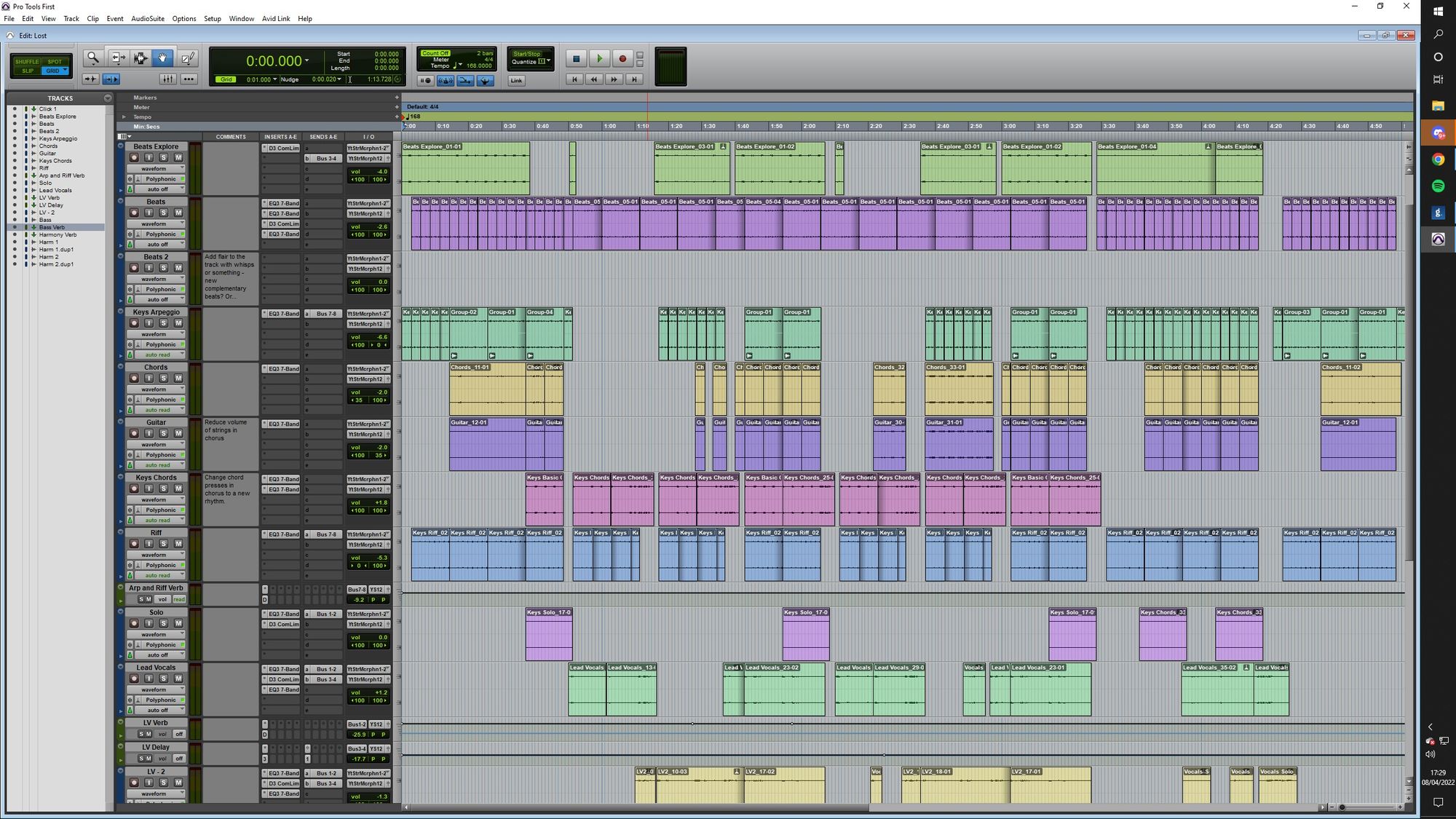

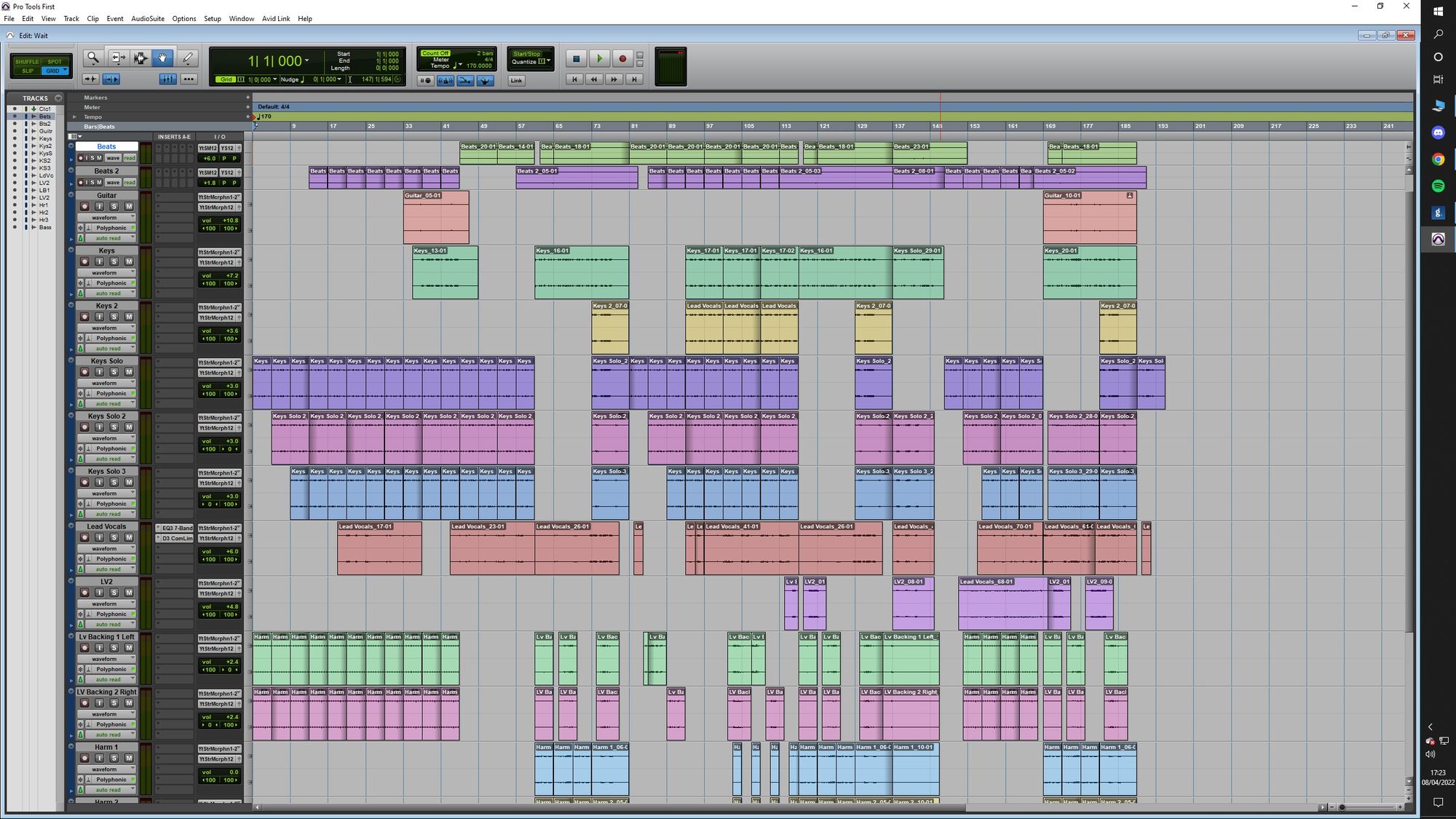

If all you have is a microphone and a keyboard, and the limitation of 16 tracks that free music software Pro Tools First provides, I’ll show you how to make a song with 16 tracks.

Limitation breeds creativity. This is true in any artistic medium, and none more so than in music. If we think about how many iconic video game soundtracks came from the Game Boy, which had only four audio channels, then we can see the possibilities of being limited in our music production.

Music production is not cheap. Expensive equipment and software (Digital Audio Workstations or DAWs) can make the financial barrier to creating music difficult to cross.

But good music can be made without spending the big bucks. Good music can be made with limited tracks and equipment. Whether you want to produce a demo track or a full song, making music with limitations can be a great first step to music production. It helps realise the core elements of music making, develops your creativity, and can help you decide whether you want to pursue producing further by investing in the more expensive side of music production.

In this post I’m going to show you how you can make your music sound full without needing to buy industry leading music software. If all you have is a microphone and a keyboard, and the limitation of 16 tracks that free music software Pro Tools First provides, I’ll show you how to make a song with 16 tracks.

Writing and Planning

While making music is an iterative process, when it come to having these limitations, planning can be crucial. Writing all or at least most of the song ahead of moving into production is vital because it can help you decide what tracks will be required during production.

For instance, what instruments will you need in your song? Will you need a track for guitar, one for bass, one for keys, one for a synth? How will this factor into your solos? If you find that you won’t need much outside the sound of keys/synths, then how do we allocate tracks for arpeggios, melodies and riffs? These are questions that are considered in any music production but become more important when you need to prioritise under limited tracks.

A good place to start is to consider what instruments are generally used in the music you are trying to make. If you were to make a pop song, then you may want at least one track for a synth, one track for bass, one track for piano, one track for guitar, and one track for the drums (we’ll come to the drums later).

With these instruments as a basis, do you have any riffs that will play over chords? You’ll need another track for these. It’s important to consider what you’ll need here as you won’t have the luxury of adding more parts when ideas come to you during the recording and production process.

The next thing to consider is about the type of chords you’ll be using. Often the temptation when writing music is to use one section of the keyboard for your chords, perhaps in the range of the C3-C5 keys. But in trying to create a full sound, utilising the range that the keyboard offers is critical and can make up for a lack of instruments to fill the space.

Recording an audio track will not work in the way MIDI does, where you can record over with more notes and combine them together. You’ll have to record extensions of chords you cannot reach onto another track. A workaround for this will be that you can record a piano chord extension, for example, in the synth track. It may not be a professionally-advised route to go down, but working with limited tracks necessitates this and can still sound strong in a mix that will likely have simple equaliser and reverb which won’t distort the sound too much.

The tracks required here should of course be suited to everyone’s individual songs. Some songs may only require a few tracks for instruments, being heavily led by slow, powerful piano chords. Others may be upbeat 80s pop tunes that require more instrument tracks to ensure that a full sound comes from a plethora of different instruments.

One of my own tracks is built around three harmonising piano riffs, taking up three tracks and forcing me to rely on a different approach to what instruments I can use in the song. Every song will be different, but if you follow the approach of planning before you start, you should find that you’ll be better equipped to create a song with such limitations.

Key Techniques

A vital part to creating full-sounding music will also come from the tried and tested production techniques, panning and double tracking. Panning is a production process where the audio levels are changed depending on the left and right outputs (i.e., your headphones/speakers). The effect will be that if audio is panned 100% to the left, you’ll only hear that audio come out the left earphone. If audio is panned 75% to the left and 25% to the right, you’ll hear the sound come through somewhere in the left side of your headspace.

Double tracking is recording process where the same line (usually vocal but in our case it can be used for instruments) is recorded twice. You might think that double tracking sounds like duplicating a line, but it is very different. When a line is duplicated, the volume will only increase. However, when you double track a line you are intentionally preserving the minute details of the change in recording. This is not about increasing the volume, but increasing the fullness of the audio to make it sound like more voices (again, usually) are contributing to the sound.

Using these techniques in tandem also creates a deep power to the sound that fills the mix and feels like the sound is being supported from beneath.

Vocals

In an exercise where all audio is being recorded through a microphone, and with limited tracks, vocals play an important role in determining whether the song sounds like a hollow conflation of instruments or a powerful symphony of sound.

In the same way that we need to think about instruments before recording and producing, so too should we think about vocal tracks. A great system I’ve found for creating music with limited tracks has been to have eight vocal tracks. These include:

o One track for your main melody

o One track dedicated as a double track for your main melody

o An optional vocal track for riffs

o Two tracks for double tracking and panning an underlying melody or strong harmony

o Three tracks for providing triad harmonies

Having your melody track in any song will be a must, but a double track can also go a long way in providing a fullness to the sound of your song and emphasising certain phrases of your melody. Double tracking the chorus is where I would apply this the most as it helps distinguish it from the verses which will often want a quieter and more focused vocal line.

Earlier I mentioned that combining panning and double tracking can have a powerful ambient effect to the sound, which is why I have dedicated two tracks to this for your song. Usually, you want to find lyrics that can be emphasised with a deeper sound or a section which may be feeling empty with a solo melody. Here you can use a double track harmony to support this or give emphasis to the section by adding a new melody that feels like it comes from further back in the mix.

The last three harmony tracks are also of vital importance. These tracks can be essential for uplifting the sound of the song. Underneath verses or choruses having simple oos that follow the chords might seem cheesy, but it really provides a strong base of support to the rest of the mix which may otherwise feel empty. You can even take a hand from a capella arranging and try to diversify your harmonies by incorporating lyrics and melodic lines that provide new textures, moving away from what may feel like quite static chords.

Recording

Aux resident Joe Belham has already provided some fantastic tips for recording instruments and vocals in previous Connect posts but I’d like to provide some further ideas for recording with the limitation of 16 tracks.

Since you’ll be recording live instruments into the microphone, it needs to be placed slightly further from the instrument than when you would be singing into it. If your microphone also has different recording settings, changing it to record from all angles can actually be beneficial in this case, which is not normal when recording vocals. I’ve found that this “surround” recording provides a very slight delay effect and can lend itself to making the instrument sound bigger than it is.

When it comes to recording the vocals, ensure that the microphone is taking in sound from only one direction, so that the vocals are as clean as possible – especially important when singing against live instruments.

If you have access to a drum kit and are comfortable recording live through one microphone, then that is excellent. However, I’ve found that beatboxing can be a fantastic replacement for an inability to produce drums in the DAW, or for recording live drums (which can get messy on one microphone). Recording beatboxing allows you to get a nuanced sound not heard much in music, but also utilises the power of only having one mic to the fullest.

You don’t have to be a beatboxing pro either - if you can learn a simple kick, high hat and snare, then you’ll be able to get a strong rhythm section that won’t sound distant and levelled strangely like you may find with drums. If you decide to record beatboxing, then you should place the microphone slightly to the side of your mouth to reduce your vocal plosives (those harsh P sounds that come from the kick and some snares).

Sometimes you may have everything in place – your instrument, vocal and drum tracks all complete with a full song to listen to – but it feels like something is missing. That can always be difficult to identify, but this is why I have left a couple of tracks free out of our limited 16. I’ve often found that what’s missing is ambient noise or effects. This can come in many forms, but, especially in pop songs, I like to use a “wisp” noise. Something akin to what you might hear in the build up section of Nicki Minaj’s “Starships”, or dance tracks like Becky Hill’s “Remember”. It’s not necessarily about filling the space with just anything, but being intentional about filling empty space that does not want to feel empty.

The best way to record wisps like these is to double track and pan them – it’s all about getting a full sound. Again, you don’t have to be any sort of beatboxing pro for this. Simply making a hissing sound while widening and closing your mouth will create different pitches and provide the atmosphere you are looking for to fill that emptiness.

Conclusion

The methods of planning and recording I’ve described are not set in stone and will be different depending on the song you’re making - you may even have a track or two spare. Maybe you can find another intricate rift to pan to one side, maybe you can add another vocal track for a short melody or to riff over something else. Maybe you even want to add some more vocal effects to spice up the song and give it a unique sound.

16 tracks may seem like a limitation, but great music can be made with it. You don’t need the best equipment, the best microphone, an expensive DAW, or to record instruments through MIDI. Whether you’re making a demo track or a full song, no matter what, the possibilities of 16 tracks are endless.