The Limitations of Intellectual Property in the Music Industry

At its core, I can’t think of anything wrong with the idea of intellectual property or copyright. But unfortunately, the realm of music is more abstract than the realm of glass and copper wires. Grey areas are the daily agenda.

If you’re keen on keeping up to date with music industry news, you’re a bit weird.

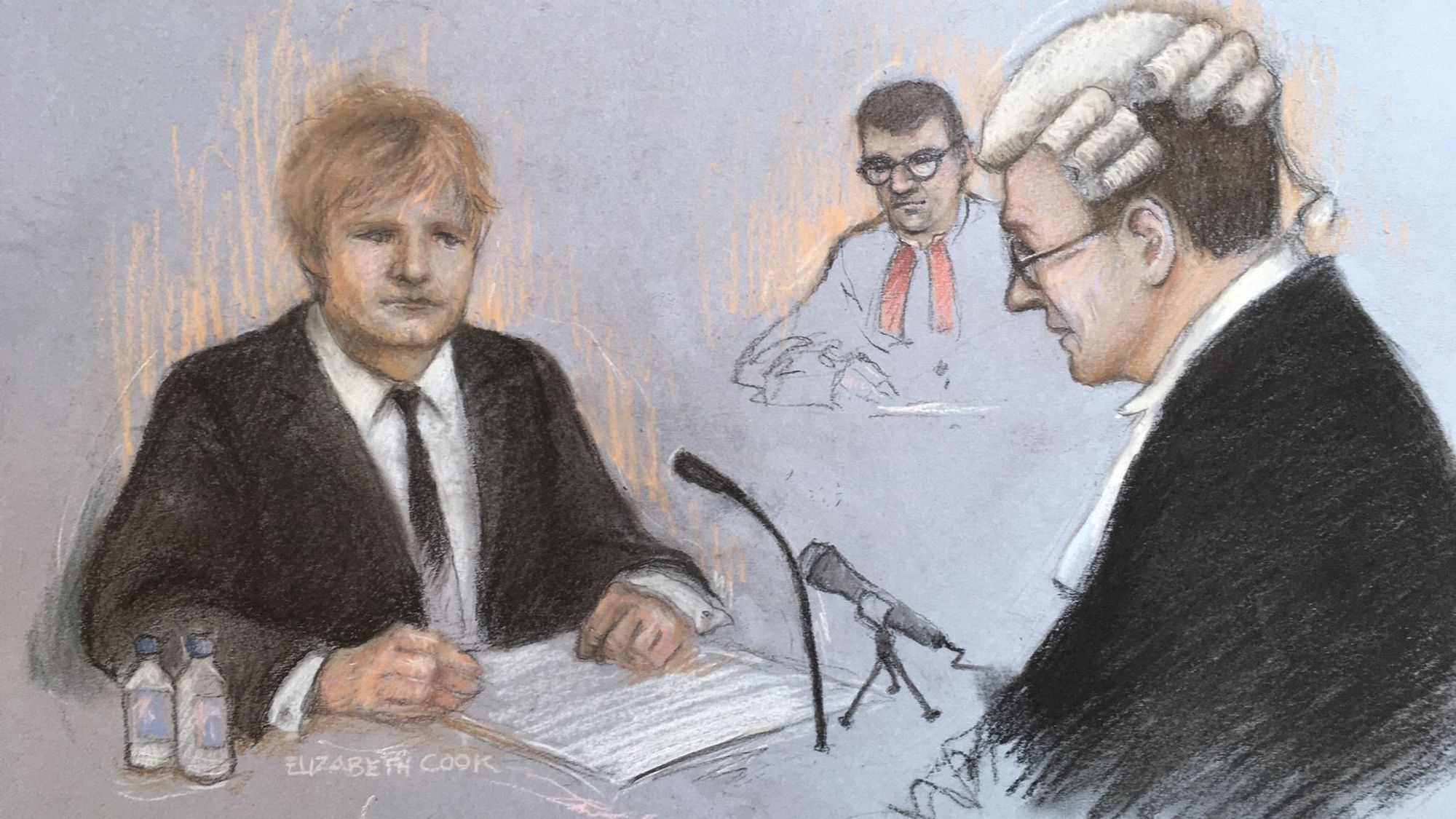

But you also might have noticed a surge in copyright infringement claims in recent years. You probably heard of a recent court case, where fellow nobody Mr. Ed Sheeran was accused of ripping off Sami Chokri & Ross O’Donoghue’s 2015 song ‘Oh Why’, allegedly stealing one of its motifs for his own track ‘Shape Of You’.

The Ed Sheeran lawsuit comes at the tail end of a barrage of similar claims, which have involved Led Zeppelin, Lana Del Rey, Robin Thicke & Pharrell Williams, among other noteworthy names.

While it’s not up to me to pass judgement on the veracity, the meaning, the logic or – quite frankly – the ridiculousness of some of these claims, I can’t help but sit on top of my ivory tower and deliver a unifying sermon as to how this phenomenon could cause some serious damage to the recorded music industry.

At its core, I can’t think of anything wrong with the idea of intellectual property or copyright. I invented the lightbulb. I patented it. You stole my idea. I sue. You pay up. I get rich. You’ll think twice before stealing again. World order restored.

That all sounds great. But unfortunately, the realm of music is more abstract than the realm of glass and copper wires. Grey areas are the daily agenda.

Take the Led Zeppelin vs Spirit case of 2014, for instance. Led Zeppelin were accused of ripping off the distinctive descending chromatic riff at the beginning of Stairway to Heaven (1971) from Spirit’s track Taurus (1968). Have a listen for yourself

The similarities are crystal clear. I jumped off my seat when I heard Spirit’s track for the first time, falling down a rabbit hole of deception and betrayal, like Caesar in his final moments. I couldn’t believe that the quintessential magnum opus, the musical equivalent of the Mona Lisa, the paramount expression of pure sonic excellence – was stolen from a band no one’s ever heard about.

Long story short, Zeppelin were off the hook after a six-day trial in 2016, with the judge claiming that “descending chromatic scales, arpeggios or short sequences of three notes” were not protected by copyright. Funnily enough, it turned out the judge’s statement wasn’t entirely right, so the verdict was overturned in 2018. In March 2020, a US appeals court has reinstated the original 2016 verdict, meaning Spirit’s only remaining recourse would be the US Supreme Court.

As similar as the two songs are (for a portion of the intro), I had to come back to my senses, realising there is much more to a song than a descending chromatic scale. As Ed Sheeran said during his trial “There are only so many notes and chords used in music. Coincidences are bound to happen”, especially if “60,000 songs are being released on Spotify every day”.

The idea of this phenomenon becoming the new normal frightens me. The risks certain people are willing to take on the basis of a brief succession of notes or chords say a lot about the current state of the music industry. Suing someone because they “stole some notes” from you seems crazy enough. The fact that so many people are doing it seems even crazier.

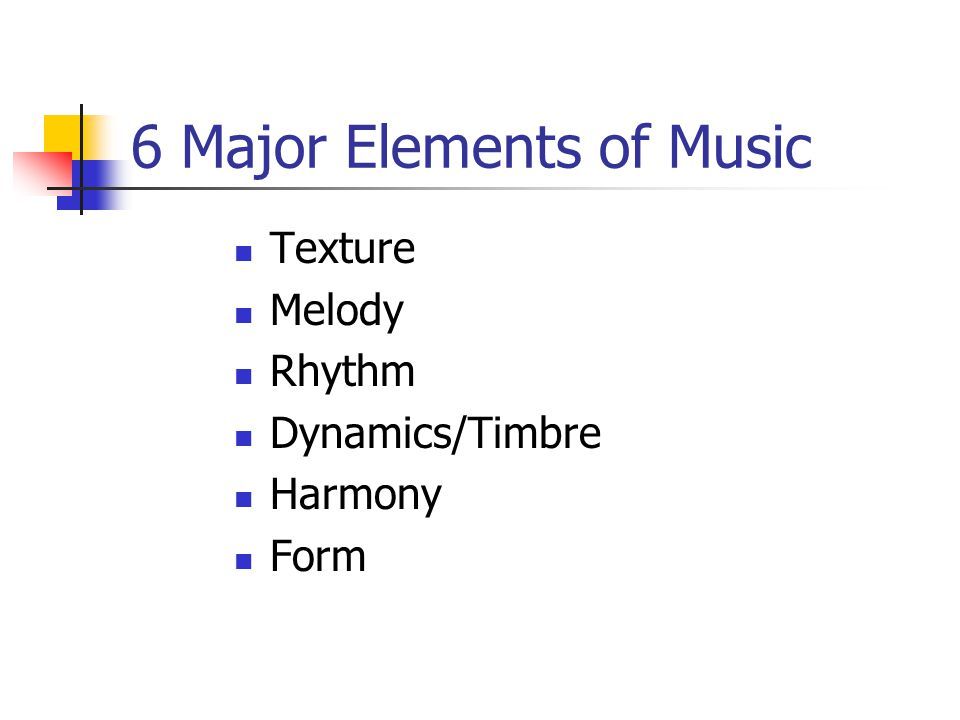

The melody, the riff or the chord progression is a relatively small part of what constitutes a piece of music. Nonetheless, people only seem to go to court over a melody or a riff. What about the timbre, the texture, the pitch, the tempo? I’ve never heard of anyone accusing someone of stealing their tempo. That’s because there is only so much you can do with these elements. The general consensus is that such components are part of the public domain. How is it any different with a melody?

The spectrum of choice for each musical element is pretty narrow. What makes it wide is their creative combination. So, you might think that Led Zeppelin ripped off Spirit, but when you consider all the elements that make music, music - you understand how different these songs are.

UK copyright law states there’s no precise rule as to how many notes in sequence one can “borrow” from another song. What constitutes copyright infringement is the copying of “the work as a whole or any substantial part of it”, which makes things a tad confusing - as there is no objective criterion that quantifies the originality of a body of work. Copyright infringement claims are usually evaluated case-by-case.

On the matter of copyright infringement claims, US music biz lawyer Robert Jacobs stresses out the frequent unpredictability of judges and juries, pointing out how - often - courts allow cases to go forward “merely based on the works at issue sharing a common ‘feel’ or using common musical building blocks that belong to no one”.

Like a descending chromatic scale.

The wishy-washiness of music copyright law has legitimized people to sue over menial, irrelevant similarities which are often variations of simple scales or modes one would learn of in their first music theory class.

What worries me about the volume of these claims is the disincentivizing effect it can have on musicians current and future, ultimately posing a threat to people’s creativity.

A musician’s subconscious plays an incredible role in the creative process. Everything an artist experiences is processed and re-elaborated in the mind. To the point where most ideas are a result of already existing ideas. To put it bluntly, nothing is really original.

That is not to say that copyright law shouldn’t protect musicians. On the contrary, recording artists should own the rights to their work, never to be copied without the intervention of the stern brass knuckles of the law.

But the powers that be should keep in mind that inspiration is different to plagiarism, and if people keep getting sued for writing songs with superficial similarities to other songs, no one will ever want to make music in the first place.